James Quinn is the writer and director behind Sodom & Chimera Productions and their upcoming film Daughter of Dismay. Quinn has been solidifying his position in the film community over the last few years since the company launched with it’s debut film The Law of Sodom in 2016. I’ve found his work very compelling and have been following the company for the last few years. But, it seemed like things were really starting to take off in 2018. This is, indeed, the perfect time to speak with James Quinn. As industry renowned talent is being brought on board for post-production and the film gets closer to completion the scale and quality of what he’s orchestrated has become apparent. This is a huge step forward for a small company, which could see themselves moving toward ever loftier goals in the film industry over the coming years. I hope you’ll enjoy my interview with James Quinn, and that you will find his work as compelling as I have!

Krist Mort as The Demon

Interviewer: Michael Barnett

Interviewee: James Quinn

Michael: The end credits for The Law of Sodom looked a bit like those of Lynch’s Eraserhead. James Quinn, you seem to have carried most of the weight of Sodom & Chimera in its earliest incarnation. Was this something you enjoyed? Do you consider yourself an auteur, more than a compiler of elements, a true author of a production?

James: The Law of Sodom (2016) was a very personal and extreme project, both in terms of content and how it was made. A lot of time and pain went into it, and it’s indeed a production that I practically carried alone entirely. By now, the way I make films has changed dramatically. I do consider my projects to be somewhat of auteur works though. My ideas and concepts of films are things I’m very picky and strict about in terms of execution, and in most cases, what you see on screen is based on deep, personal ideas and emotions, things I try to convey in very specific ways. Though, it has to be made clear that all films are collective works, larger ones often more than smaller ones.

Regarding Eraserhead (1977), yes, that has always been a massive inspiration to me as a filmmaker, and has also influenced the making of The Law of Sodom.

Michael: How long has Sodom & Chimera been active? Was it long before the release of The Law of Sodom, or was it a fast-moving project from the very beginning?

James: Sodom & Chimera is fairly young. It was founded in October 2016, right after the North American premiere of The Law of Sodom, which was shot before Sodom & Chimera was a thing. Sodom & Chimera, to me, is more of a personal collective. We’re a small team, and work together on a lot of projects, but most importantly, it’s a way to connect all works, promote them, and give them a voice under the banner of something more recognizable than just the name of a director. Sodom & Chimera represents a large body of work, from photography to film, to the occasional other obscure piece of art that might present itself. It has indeed always been a very fast moving project, from the day it started.

Michael: What have been some of the biggest influences on the people behind Sodom & Chimera? Do you have a personal favorite director?

James: I can’t speak for my colleagues, but personally, there are only a handful of artists that directly influenced me. The very obvious one is David Lynch, though – even though I greatly enjoy all of his works – the only of his films that directly affected my own filmmaking are Eraserhead and Inland Empire (2006). Other big influences in terms of more obscure works have been Karim Hussain’s Subconscious Cruelty (2000), Merhige’s Begotten (1990), Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), Un Chien Andalou (1929), Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009), and several works from the 20s and 30s. Even though a lot of my previous films are very bizarre and surreal, the grotesque aspect of them was never my true objective. It was important to me, yes, but my main goal was always to create something that is beautiful or at least interesting to look at. Cinematography is the most important element in all of my films, it’s a tool I use not just to show what’s happening in a scene, but to be poetic and create impressions that stick out. To be completely honest, most of the ways I frame shots and try to explore visuals do not stem from inspiration from certain films or photography, but from paintings. Paintings are built differently, from the way they’re framed to the amount of detail present, to just how much image is included in the frame and where it cuts off. Creating images like this is a very mathematical process, actually. I try to keep that in mind whenever I build a scene.

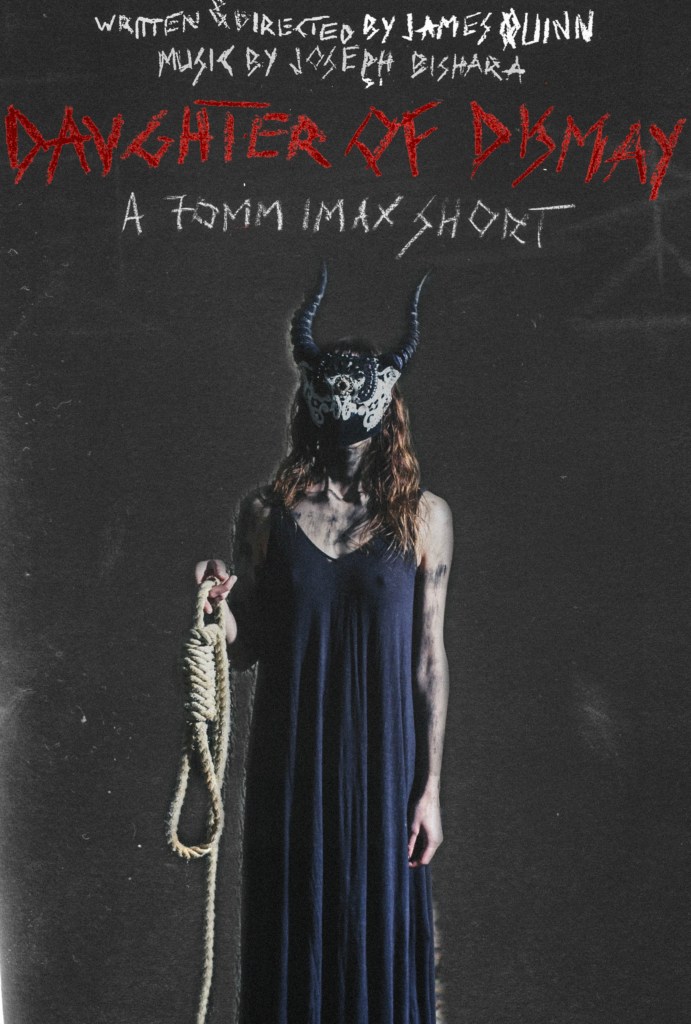

Ieva Agnostic as The Witch in Daughter of Dismay

As to the question of who’s my favorite director, that’s an easy one, actually. Andrei Tarkovsky. Never have I seen any other works of film in my life that convey visuals like his. It’s pure cinematic bliss to me, and all of his films are truly like moving paintings. Having seen his film Andrei Rublev (1966) on 35mm, I don’t think I’ll ever change my mind on who my favorite director is.

Michael: Daughter of Dismay has been moving along nicely, with some great talent steadily being added to the project. How much work is going into this one in comparison to previous films?

James: Daughter of Dismay is a mammoth of a project that pretty much destroyed my health. There was so much careful planning, budgeting and pitching involved, so many days of going without sleeping, so much unbearable stress that I literally had to call an ambulance to my house due to heart problems a week after the shoot was over. I’m still recovering, even though production is nowhere near over. Once post is finished, the entirety of the production will have taken around a year, of which only two days were shooting. Shooting a short in 70mm IMAX, actually getting it made is pretty much near impossible, and it has a reason no one has done it yet. Getting closer and closer to the finish line of post production, I can see why no seems to have even attempted it yet. It completely eviscerated me, mentally and physically. But it was entirely worth it.

James Quinn

James Quinn

Michael: Do you anticipate Daughter of Dismay to be a more or less accessible (in terms of theme/content) film than your previous works?

James: Daughter of Dismay is supposed to be a film that can be enjoyed by the masses. It’s the most accessible film I directed so far, and can be enjoyed by pretty much anyone who is okay with darker themes. It is indeed extremely dark, emotional and sad, with one scene that might make some cringe, and the tone is very sinister, but in its core, it’s a very inspiring story with an extremely polished look. It’s not experimental in the slightest and presents itself in a very linear manner, with a focus on epic, visceral execution. We had an extremely large budget, which enabled us to get the most out of this and make it feel like a little blockbuster, instead of just an independent short, for which I’m very thankful. The reason I made the film this way is multi-faceted. I love creating dark niche visions, films that freak people out and evoke extreme reactions, raw, experimental films that mess with people’s heads, but I’ve also always particularly enjoyed the kind of cinema that relies on entirely different values; clean, more traditional pieces of direct storytelling, with a strong focus on emotion, something that progresses throughout the story and ends with a bang, a scene that leaves you emotionally affected while watching the credits roll. This is a recipe that works especially well with short films, one that I’ve been meaning to explore for a while, though never had the means to properly pull off. Some of the fans of my work might get cramps reading this, but Daughter of Dismay was made to be mainstream-accessible, which is one of the reasons we shot in IMAX, and will present it in this format. It’s supposed to be big, epic, dramatic and to be enjoyed by as many people as possible, though in this case not for being “fun”, but for the intense impact it has. Even though it is so very accessible, I still have to clearly mention that I included a lot of my trademark elements in the film, and it is guaranteed to be the darkest and most surreal IMAX film you’ve ever seen.

“I love creating dark niche visions, films that freak people out and evoke extreme reactions, raw, experimental films that mess with people’s heads, but I’ve also always particularly enjoyed the kind of cinema that relies on entirely different values; clean, more traditional pieces of direct storytelling, with a strong focus on emotion, something that progresses throughout the story and ends with a bang, a scene that leaves you emotionally affected while watching the credits roll.”

Michael: What is the most crucial change in the framework this time around? Someone added to the project of utmost importance or some perfect set location?

James: Everything was different about this project, and every single thing mattered. From the gigantic efforts our cinematographer took upon himself, making sure to pull this off in the most amazing way possible, and enabling us to shoot in IMAX, to the lighting team, who pulled off the insane task of shooting with an ISO of 50 in a location with barely any light, and made it look like the sun was shining intensely, to our special effects team, who built an entire fake human that looked completely life-like, to our incredible team of production assistants, we went big in every single aspect of the production and squeezed out every drop of potential there was, to make it the film it is now. It would be hard to pick something precise, something that I can point to specifically, since every single aspect of the film’s production was extremely important, and if just one were missing, the film wouldn’t exist.

Dajana Rajic on Daughter of Dismay set.

Michael: For Daughter of Dismay, are there any connections to previous films you’ve produced? What should the viewer know, going into the film?

James: I would actually go as far as to say the ideal way to watch this is without having seen any of my other work before. It has no connections whatsoever to the rest of my films, and is very different, in that it is just a lot less offensive or extreme, and, like mentioned earlier, much more accessible than anything I’ve ever done. So, having seen the rest of my work, one might get false expectations, which is one of the reasons I’m making it very clear that this is a cleaner version of my artistic vision, though I do think fans of my traditional work will enjoy it just as much. If you go into this not knowing anything about it, or about my work, you’ll be able to enjoy it unbiased, just knowing you’re going into a 70mm IMAX film, which I think really helps.

Michael: You created the film in 70mm, and appear to be one of the first in the industry to do so for a short film. What influenced this decision and what is so important about working in this format as opposed to the industry standards?

James: We’re the first narrative short film in the history of cinema to shoot in 70mm IMAX, actually. Most films that have been shot this way are either grand space documentaries, or other documentaries of gigantic proportions, or massive blockbusters like Dunkirk (2017) or The Dark Knight (2008). The reason we shot in this format is quite simple: It was clear pretty early on that Daughter of Dismay is supposed to be a big, epic piece of film, something you watch and go “wow”, something you don’t just watch, but actually experience. The closest experience to being inside a film itself (besides 3D, which I’m not a supporter of) is 70mm IMAX, a format that is so unlike any other format, simply due to the intensity of the image, the detail and sharpness, it’s like being sucked into the world of the film itself. Christopher Nolan very fittingly described it as “virtual reality without goggles”. You’re being moved closer to the screen, which is extremely large, not only being very wide, but multiple times as tall as regular screens, which places you directly in the center of the image. Additionally, the sharpness and detail are so intense, it makes things pop out that you would never see in any other format. The digital resolution equivalent is around 18K, something that is obviously impossible to reach with digital sensors. Actually, you see more detail in a 70mm IMAX projection than in real life. We had to stop and have someone remove a pencil from the forest ground during one scene since people would have been able to see it on the big screen. In real life, this was barely noticeable. The way we see things when looking at a two-dimensional image this sharp is vastly different from the way we see the world in real life, and it gives us a strange sensation of being “more real looking than real life”. This is exactly what I wanted for Daughter of Dismay. You don’t just go see it. You experience the entire thing. Obviously, not everyone will be able to see it in this format, but we’re going to make sure to have the rest of the presentations be as impressive as they can, which means most of them will be in regular 70mm or 35mm, both formats that are absolutely beautiful.

Michael: You filmed Daughter of Dismay deep in the woods of Austria. Was this the plan from the beginning? What are some features of the Austrian woodlands which attracted you to this set location?

James: I have always been fascinated by forest landscapes and the natural atmosphere they bring. There’s something mystical and sinister to them, even though I consider it to be a place of peace. Most of my films have scenes in the woods or take place in them entirely. The Austrian woods, besides being the most accessible to me, since Austria is my home, are especially beautiful to me. For Daughter of Dismay, I wanted a set that’s as visually impressive as possible. Fallen trees, very large, tall ones, big, thick roots, grounds full of leaves, all of this is essential to the visuals of the film. I’ve shot in many different forests so far, and all of them looked different. This time, I went back to one I’ve already shot in, for Flesh of the Void (2017), though in Daughter of Dismay everything looks vastly different due to the different format, color and style. I’ll most certainly continue to shoot in forests, though I’d love to explore different ones in the future. Getting to explore mystical locations for a film shoot is one of the many things I enjoy about filmmaking. It’s a multi-faceted process that brings me much joy.

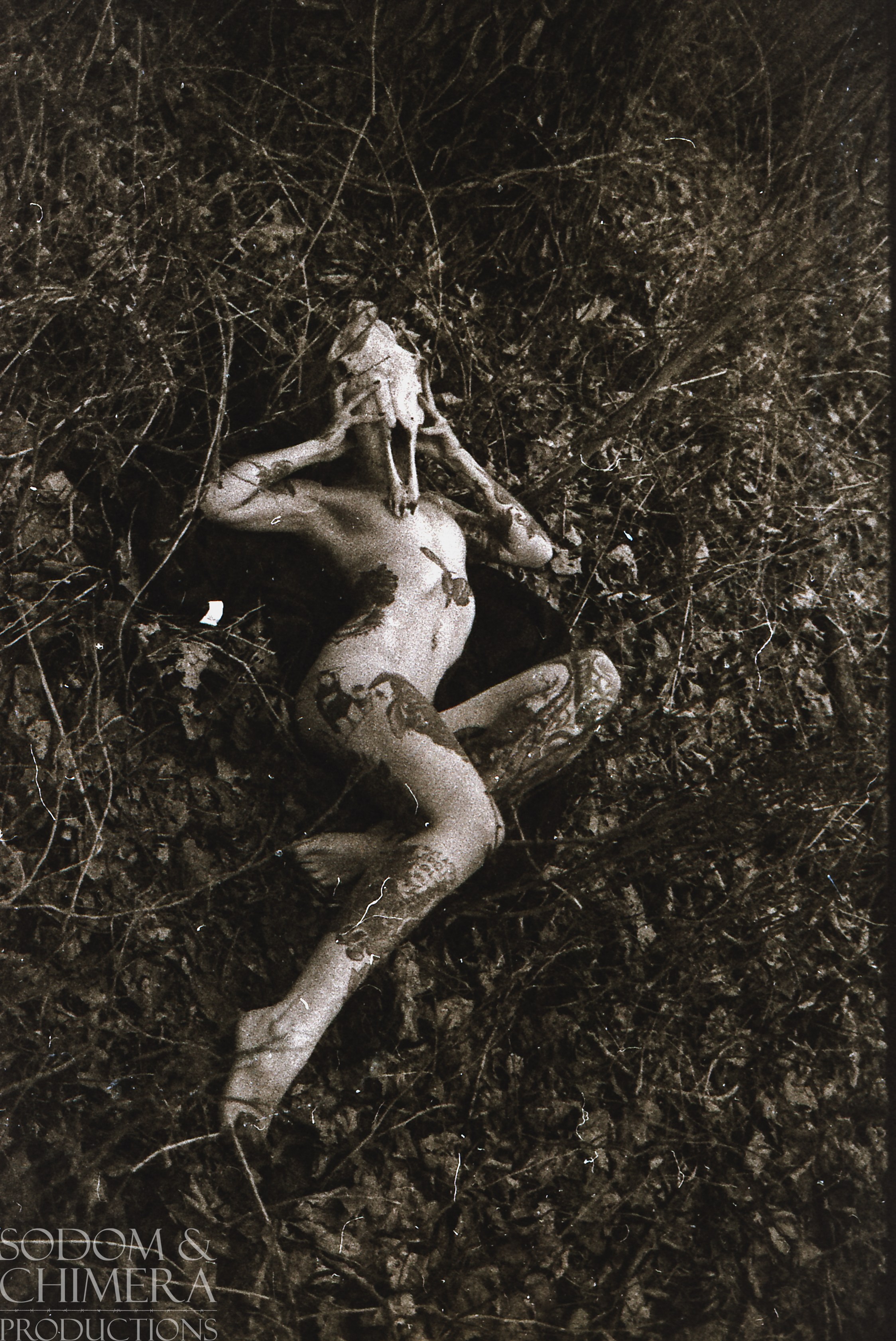

Still from Daughter of Dismay

Michael: Joseph Bishara will be working on the film score for Daughter of Dismay. What has been your past relationship with this musician? Why is his work so fitting for the film?

James: I haven’t had any sort of relationship with Joseph previous to Daughter of Dismay. He was my first pick for the film’s score, and he agreed to do it. I consider us extremely lucky to be working with him. Joseph is an absolute genius in his field and, in my opinion, one of the most talented horror composers of all time. I clearly remember seeing Insidious in the theater in 2010, and being absolutely blown away by how anxiety-inducing and dreadful his sounds are.

The screeching violins, dissonant and violent, loud, metallic explosions of piano strings, paired with very harmonic, beautiful and emotional melodies placed me in an absolute state of awe. I remember going back home, and immediately looking up the score online, listening to it again to examine it. There’s a very psychological element to Joseph’s way of composing, with an extreme amount of detail and passion present in his music, as he’s able to give you chills by simple (and also very complex at the same time) means of sound, something that deeply impressed me. I ended up following his work closely, being blown away over and over again. For Daughter of Dismay, we needed something sinister, something dark and mystical, but at the same time something that is extremely emotional, melancholic and touching, something that puts you in a certain mood by just listening to the piece itself. Knowing very well about Joe’s talent in not just creating horrifying soundscapes, but also strong emotions, I contacted him and told him about the film, and the rest is history.

Michael: Ben Brahem Ziryab has been brought on as director of photography. He’s done some quite impressive work in the past. How has your experience been working with him? Does he bring a particular magic to this project?

James: Ben was absolutely amazing to work with. He did indeed bring a particular magic to the project. Not only did he enable us to expand to IMAX instead of regular 70mm, his work ethics, dedication and talent stood out so much, I know for certain already that I will continue to work with him on more projects. He initially contacted me about a possible collaboration, and after talking to him on the phone for hours, I knew absolutely that this was going to be a person I’d want to work with more regularly. His passion for analog film and cinematography is absolutely magical, and he is talented beyond belief. I especially urge readers to check out his short The Negative (2017), which was shot in VistaVision (horizontal 35mm film). It’s an absolute masterpiece of both, storytelling and cinematography, and is deeply inspiring as a project, too. We worked together closely on Daughter of Dismay, and prepared on location for around 10 days before the shoot, visiting the set almost daily, to plan everything through as carefully as possible. Working with him on set was fantastic, as our visions for the film matched perfectly, with some of his own touch making it the unique piece it is now.

Editor’s note: You can read more about Ben, VistaVision and The Negative in this article by Kodak cameras.

Director of Photography, Ben Brahem Ziryab on set.

Michael: As for the acting talent in Daughter of Dismay, do you have any recurring actors you seek to employ for each project?

James: I try to work with new talent as often as possible. I enjoy exploring the world of actors and actresses, and there are many fantastic talents out there. I do occasionally hire people I’ve previously worked with, as I did with Dajana Rajic, who plays the daughter of the witch in Daughter of Dismay and has acted in a music video I directed. But usually, I try to focus on being open towards new talent and finding the absolute perfect persona for the character of the film. In the case of Daughter of Dismay, we had an extremely talented all-female cast. Actually, the entire reason why the film exists is due to the lead actress, who I did a spontaneous photo shoot with in early 2018, in which she posed as a witch, which lead to very occult works of photography. I was so impressed by her ability to portray emotion and expression purely through her face and posture that I asked her if she was interested in starring in a film as the same character. She loved the idea, and I was so into the character that I ended up writing the script in a couple of hours, since I already had her entire background story laid out in my head. Everything progressed from there. She really sells the film, her talent and mystical looks are perfect for this role and inspiring. Dajana, who played the role of the daughter, a smaller role, but very important nonetheless, did an equally amazing job. I love working with children, and Dajana is especially gifted at following instructions, and has an intense emotional range that she can express on command. Her role was very dependent on conveying confusion and sadness, and she proved to be absolutely perfect for it. The shot before the very last shot in the film is a shot of her that is especially haunting, though you’ll have to see for yourself why.

Dajana Rajic in Daughter of Dismay (not that final shot mentioned above).

Michael: What are some other films and projects from Sodom & Chimera which you would like to mention?

James: With the promotion and publicity of Daughter of Dismay, I’m trying to focus on presenting it as a singular project, one that’s separate from my others, like mentioned. I’ve made a range of films so far that are all very different from each other, though many carry distinctive elements that I put in all of my films. My favorite so far, besides Daughter of Dismay, was Sulphur for Leviathan (2017). It’s a grimy arthouse short about Satanism and the downfall of Christianity, and was heavily inspired by Andrei Tarkovsky. It was painful to shoot and made me want to quit filmmaking, but I’m extremely glad we pulled it off. It’s still the most provocative and radical film I’ve made so far, even though there’s practically no violence in it.

For people who would like an introduction to my filmmaking roots, I suggest to check out The Law of Sodom, which is an extremely disturbing and experimental film about my personal experience with mental illness, all written and shot during episodes of psychosis. (Watch on Vimeo on Demand)

Like mentioned though, Daughter of Dismay is a very separate piece, and I’d like for people who see it to disregard any other work they might have seen of mine. That doesn’t mean I’m not proud of my other films – not at all. It’s just such a unique and different film, I’d like people to go into it without any specific expectations of my style.

From the photo set (same name) which inspired Daughter of Dismay.

Michael: You also work within still-photography, a number of these sets are available for browsing at sodomchimera.com/photos. I particularly enjoyed the ‘Idolatry of Emptiness’ set. Is this an equal passion to your filmmaking? What has been your most memorable photoshoot?

James: Photography is a big passion of mine, yes. Visual art is something I’m very fond of, and there’s something about photography which greatly excites me, which is the ability to tell an entire story with one single frame, to put very specific thoughts into people’s brains and make them make up their own stories. There are similarities to filmmaking in the way I approach it, but in the end, it’s such a wonderfully different medium, and it’s especially pleasing as an artist since it works quicker than shooting a film. I do prepare most of my shoots, and even script them, but with photos, the possibilities of being spontaneous are much more open, and I very much enjoy that. Often, my photography is later used as the base for films, as was the case with Daughter of Dismay.

from ‘Idolatry of Emptiness’ set.

Michael: For a newcomer to the films of Sodom & Chimera, what would you recommend to readers as the best starting point?

James: I’d say check out the photography first, and start with a more stylistic and less extreme short, like Sulphur for Leviathan. It will give you a better idea of our artistic goal, after which you can work your way up to more obscure works like The Law of Sodom and Flesh of the Void. Ideally, you’d start with Daughter of Dismay, but it’s obviously going to take a little while until that’s possible.

Michael: Do you have any lofty goals for Sodom & Chimera? Any dream projects which you are waiting for the perfect set of circumstances to proceed? Or have you been steadily working through most of the ideas as they arise?

James: There are a few projects and scripts that I’m sitting on that I’m waiting with still, just because they need the right resources and talent, and I’d like them to be perfect. I can’t really say a lot about our future work, though I can tell you that there will be more features coming.

Michael: I thank you very much for your time, James. If you have any last words or information that you would like to give readers, feel free!

James: Thank you! All I want to close with is an appeal to people to go out and experience movies more intimately and intensely, and give analog film a chance. Look up special screenings, take a road trip and check out a film in 70mm IMAX, watch old classics in 35mm, take the time to experience things and movies you don’t know or maybe wouldn’t have watched otherwise, try to see the medium of film as an experience and spectacle instead of something to pass time with. It’s such a beautiful art form, and there are amazing sights and experiences to be had beyond just watching a film on a flat screen or in your local multiplex. Go live some movies.

Links

Sodom & Chimera Official Website

Facebook – Sodom & Chimera

Instagram – Sodom & Chimera